The Emissions Reduction Plan is a hodgepodge of responses from Ministers, some of whom appear to not be grappling with the very real urgency of climate breakdown, says Oxfam Aotearoa Campaign Lead Alex Johnston.

“Taking nine months to come up with a discussion document about making yet another strategy is not acceptable. With COP26 less than a month away, the government clearly isn’t taking the climate crisis with the urgency required to keep a safe climate future within reach. Aotearoa needs to do more to achieve its fair share of keeping to 1.5 degrees.

“We think of our friends, colleagues and loved ones in the Pacific and beyond who will have to continue to endure rising poverty and hunger, farmers who are losing crops, family homes being destroyed by rising sea levels, and loss of their whenua and culture.

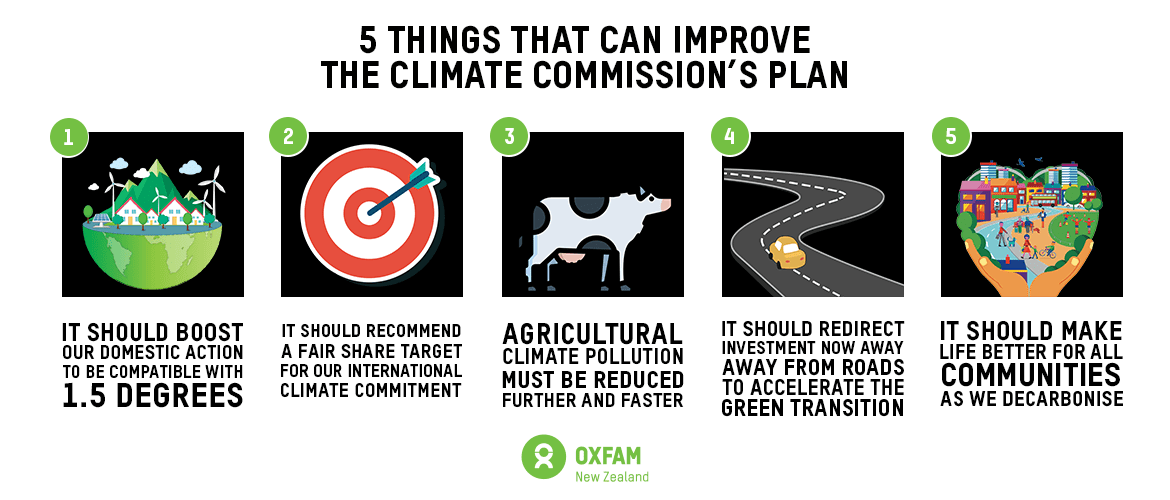

“We urge the Prime Minister to exert leadership within the Climate Change Response Ministerial Group to get Ministers to come back to the table with policy levers that will reduce emissions further and faster, while leaving no one behind. Every sector has to play its part – this includes our agriculture sector which is responsible for half of our emissions profile, but has no new reductions forecasted before 2025. He Waka Eke Noa is not going to meet the target the Government has set itself. The handbrakes need to be taken off now to allow agriculture to play its part in our collective effort to reduce emissions.

“We call on the Government to support farmers to adopt regenerative farming practices that restore soil, water and air quality, including funding to help them do this; to bring forward the pricing of agricultural emissions in the ETS; and to phase out the use of synthetic nitrogen fertiliser, which has fuelled the growth in the dairy cow numbers over the past three decades.

“It is obvious that there is a missing link between the Draft Plan and level of emissions allowed in the proposed emissions budgets. There is also a huge gap between the plan, emissions and what is needed to step up our international commitments by 2030 to keep to 1.5 degrees. Much bolder action is needed to allow our domestic plan to do more of the heavy lifting in meeting our international target, which itself is too low.

“Taking bold action to reduce climate pollution is still the best opportunity we have to create a just, inclusive and sustainable world where people and planet thrive. The solutions are in our reach, and the public will back Aotearoa playing its part to make that a reality.”