More than 300 children have died in fighting across Yemen in the year since an airstrike hit a bus in Sa’ada killing 41 school children, and almost 600 have been injured as international arms sales continue to fuel the conflict.

335 children have been killed by violent attacks including airstrikes, mines and shelling since 9 August 2018, equivalent to another eight buses being hit. Many more have died from hunger and disease, according to the UN, in a massive humanitarian crisis stoked by the conflict.

Muhsin Siddiquey, Oxfam’s Yemen Country Director said: “The world was rightly appalled by an attack that took the lives of so many young, innocent schoolchildren. Yet almost one child a day has been killed in the year since and violence remains a daily threat for Yemenis, alongside the struggle against hunger and disease.

“The people of Yemen urgently need a nationwide ceasefire before more lives are lost to this horrific conflict and the humanitarian disaster that it is fueling. All parties to the conflict and those with influence over them should do all in their power to end this deadly war now.”

Since the latest figures were published, more children have been killed or injured. Just last week an attack on a market killed at least 10 civilians, including children, in Sa’ada while in Taizz, five children were injured by shelling.

Airstrikes and shelling in Al Dale’e in May killed 10 children. In March, five children were killed in clashes in Taizz city while an attack on the Kushar district of Hajjah governorate killed 14 children. Over the year, there have been 30 incidents involving schools and 18 involving hospitals.

The conflict, between the Houthis and the internationally recognised government, backed by an international coalition that includes Saudi Arabia and the UAE, is now in its fifth year. The United Nations has estimated that if the war continues until 2022, more than half a million people will be killed by fighting, hunger and disease.

The Houthis and the internationally recognized government of Yemen reached an agreement at talks in December which included a ceasefire deal for the key port of Hudaydah but moves to implement it have been long delayed.

The government and the Saudi-led coalition have accused the Houthi forces of over 5000 violations of the Stockholm agreement, while the Houthis have in turn blamed the coalition and government forces for more than 27,000 violations.

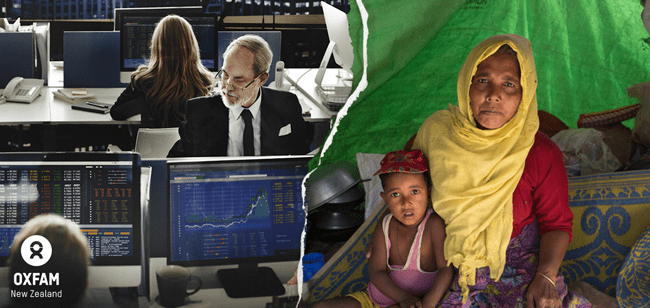

The international community is coming under increasing pressure to stop selling arms to Saudi Arabia and other members of the coalition.

Siddiquey said: “Seventy years after the creation of the Geneva Convention, which seeks to protect civilians in and around war zones, children in Yemen still find themselves in the firing line.

“The international community should focus on protecting the lives of Yemeni civilians and ending this war, not profiting from it through arms sales.”

Notes:

- Data on the number of children killed and injured has been provided by the UN Civilian Impact Monitoring Project (CIMP). It is unverified open source information. The Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED) and the Yemen Data Project also monitor civilian casualties. None is an official source and given the difficulties of working in Yemen, the data from these three sources do not always match.

- The CIMP data shows 335 children died and 590 were injured between 9 August 2018, when the bus attack in Sa’ada took place, and 3 July 2019.

- The government and coalition allege over 5000 violations of the Stockholm agreement by Houthi forces since it came into effect on 23 December 2018 until 10 June 2019. The Houthis allege 27714 violations by the government and coalition in the period 23 December 2018 to 2 July 2019.