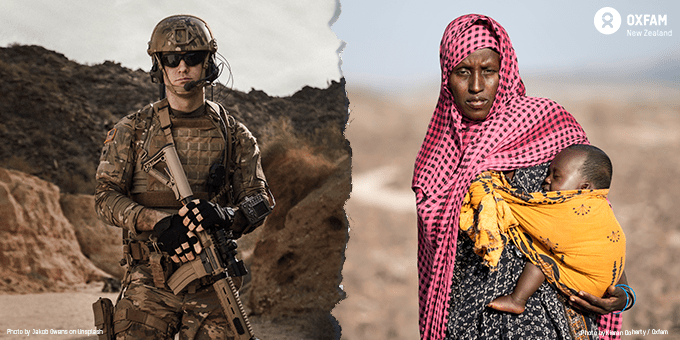

Only 26 hours of global military spending is enough to cover the $5.5 billion needed to help most at risk

A year on since the UN warned of “famines of biblical proportions”, rich donors have funded just 5 percent of the UN’s $7.8bn food security appeal for 2021.

More than 200 NGOs published an open letter today calling upon all governments to urgently increase aid to stop over 34 million people, from being pushed to the brink of starvation this year.

The $5.5bn additional funding recently called for by the UN WFP and FAO is equivalent to less than 26 hours of the $1.9 trillion that countries spend each year on the military. Yet, as more and more people go to bed hungry, conflict is increasing.

At the end of 2020 the UN estimated that 270 million people were either at high risk of, or already facing, acute levels of hunger. Already 174 million people in 58 countries have reached that level and are at risk of dying from malnutrition or lack of food, and this figure is only likely to rise in coming months if nothing is done immediately.

Globally, average food prices are now the highest in seven years.

Conflict is the biggest driver of global hunger, also exacerbated by climate change and the coronavirus pandemic. From Yemen, to Afghanistan, South Sudan and Northern Nigeria, conflicts and violence are forcing millions to the brink of starvation.

Many in conflict zones have shared horrifying stories of hunger. Fayda from Lahj governorate in Yemen says: “When humanitarian workers came to my hut, they thought I had food because smoke was coming from my kitchen. But I was not cooking food for my children – instead I could only give them hot water and herbs, after which they went to sleep hungry. I thought about suicide several times but I did not do it because of my children.”

At the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic the UN Secretary General called for a global ceasefire to address the pandemic but too few leaders have sought to implement it. Global leaders must support durable and sustainable solutions to conflict, and open pathways for humanitarians to access those in conflict zones to save lives.

Amb. Ahmed Shehu, Regional Coordinator for the Civil Society Network of Lake Chad Basin said: “The situation here is really dire. Seventy percent of people in this region are farmers but they can’t access their land because of violence, so they can’t produce food. These farmers have been providing food for thousands for years – now they have become beggars themselves. Food production is lost, so jobs are lost, so income is lost, so people cannot buy the food. Then, we as aid workers cannot safely even get to people to help them. Some of our members risked the journey to reach starving communities and were abducted – we don’t know where they are. This has a huge impact on those of us desperate to help.”

/ENDS

Notes to the editors

- The open letter can be found here: https://www.icvanetwork.org/SignOpenLetterFaminePrevention

- In the first quarter of 2021, donors have provided just 6.1% of the total $36 billion requested in the UN humanitarian appeals for the year. In the food security sector, donors met only 5.3%or $415 million of the total $7.8bn requested. (As of April 7, 2021)

- The military spending figures are based on 2019 report by theStockholm International Peace Research Institute which estimated global military spending at $1.9tn.

- According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), world food prices stood at their highest level in seven years in February 2021

- The study by Development Initiatives of the impact of COVID-19 on aid levels, found substantial declines in aid commitments in 2020 for Canada, Germany, the UK and the US, and a small decline for EU institutions. No data are provided on France, Italy and Japan.

- The latest figures on global hunger levels are as of of March 2021 from FAO-WPF’s Hunger Hotspots report In December the UN’s Global Humanitarian Overview for 2021 warned the number of acutely food insecure people could rise to 270million by the end of 2020. FAO & WFP echoed this estimate in their call to action to avert famine in February 2021.

QUOTES FROM NGO SIGNATORIES:

David Miliband, CEO and President of the International Rescue Committee, said:

“The worsening rate of global hunger is horrifying to witness. Every day we are seeing the human cost of hunger play out in the countries where we work. World leaders must act now to prevent unprecedented levels of suffering, through increased funding and diplomatic efforts to end conflict and improve humanitarian access.”

Oxfam International Executive Director, Gabriela Bucher said:

“The richest countries are slashing their food aid even as millions of people go hungry; this is an extraordinary political failure. They must urgently reverse these decisions. And we must confront the fundamental drivers of starvation – global hunger is not about lack of food, but a lack of equality.”

CARE International Secretary General, Sofía Sprechmann Sineiro said:

“Whether Yemen, Syria or the DRC, funding to respond to the hunger crisis is not materializing. Yet trillions are invested in rescue packages for corporates all over the world. Donors must step up. It is not a matter of affordability; it is a matter of political will. CARE’s evidence base tells us that for every dollar women earn, 80 cents go back into the family, compared with 30 cents of every dollar men earn. Gender inequality is a key predictor of the occurrence and recurrence of armed conflict. If we fail to grasp this simple fact, we will fail to prevent or effectively counter famine.

Save the Children’s CEO, Inger Ashing said:

“We have warned donors over and over again – their inaction is leading to death and despair among children, as we see in countries across the globe every single day. A pledging conference for Yemen in early March did not even raise half of the funds needed, and that country is at a tipping point. It’s painful, because governments have the money. That thousands of children will be dying of hunger and disease in 2021 is a political choice – unless governments radically choose to help save the lives of children.”

The Danish Refugee Council Secretary General, Charlotte Slente said:

“Among the growing number of refugees and displaced persons, lack of access to food severely worsens an already critical situation. DRC calls on all governments to act now to prevent global hunger from adding further destitution to the world’s most vulnerable groups of people.”

World Vision International President & CEO, Andrew Morley said:

“Let me be direct: there is no place or excuse for famine in the 21st century. The fact we have reached this point shows there has been a clear and catastrophic moral failure by the international community. A generation of girls and boys needs us to bring hope, supporting and empowering them to reach their full potential. Children of the world are looking to us to act.”

Interim CEO of Islamic Relief Worldwide,Tufail Hussain, said:

“Cutting aid in the middle of a pandemic is morally abhorrent and risks rolling back decades of development. Failure to act now will cast a shadow over generations to come, as malnutrition affects young children’s cognitive and physical development for the rest of their lives. The world must not wait for famine to be declared before helping people who are starving right now. We are calling for global solidarity to end hunger and stand with the world’s poorest people.”

Anne-Birgitte Albrectsen, CEO of Plan International, said:

“We are witnessing a devastating global hunger crisis, which will hit girls and women the hardest. In countries like South Sudan, we are already hearing reports of hunger-related deaths and families going entire days without food. Others are making heartbreaking choices, marrying their daughters early or saving what little food they have for working members of the household. It is critical that world leaders step up and provide more funding for humanitarian assistance – otherwise, we risk millions of avoidable deaths.”

Media Contact:

Jo Spratt | Communications and Advocacy Director | Wellington, New Zealand | [email protected] | 0210664210