“I had tears in my eyes when I saw my flooded home and village. Every time I think about my life before our village was flooded, I long to go back to that time.”

— Bong Kheun, resident of Srekor village, now fully submerged by the Lower Sesan 2 Dam

“We, community members affected by the Lower Sesan 2 Hydropower Project in Stung Treng Province, Cambodia, are writing to you to seek your assistance in addressing our ongoing concerns about the Project and the impacts it has caused to our lives. We understand that VietinBank is a key shareholder in the joint venture company that owns and operates the project…”

— Letter from affected communities to VietinBank, November 2020

The grim story of the communities affected by the Lower Sesan 2 dam, a hydropower project in Cambodia, is but one of many – a familiar cycle of inadequate consultation, lack of fair and appropriate compensation, and forced displacement from ancestral homes, property, and livelihoods under extreme pressure. Compounding these issues is lack of access to the basic information of who is funding the project that is irrevocably altering the lives and future of their communities. The Lower Sesan 2 Dam is being partly funded by VietinBank and ABBank, two financial intermediary (FI) clients of the International Finance Corporation (IFC). It was only through the support of international NGOs with access to financial databases that the communities affected by Lower Sesan 2 discovered the financial link to the World Bank’s private sector arm and filed a case at its accountability mechanism in 2018 – years into their attempted engagement with project financiers.

Another example is a recent complaint filed at the Independent Complaints Mechanism (ICM) describing how FirstRand Bank’s investment in New Liberty Gold Mine is linked to significant environmental and social impacts on several communities in Liberia. FirstRand Bank is a financial intermediary of Germany’s DEG, France’s Proparco, and FMO from The Netherlands, three European based Development Finance Institutions (DFIs). Community leaders in Liberia say the mining company has taken their homes and farms, polluted their water, and broken promises to provide jobs, schools and other facilities. Another common trend between these two cases is that it was difficult for affected communities to know who are the financiers behind the project that is affecting them, let alone what protections they have and how to seek redress.

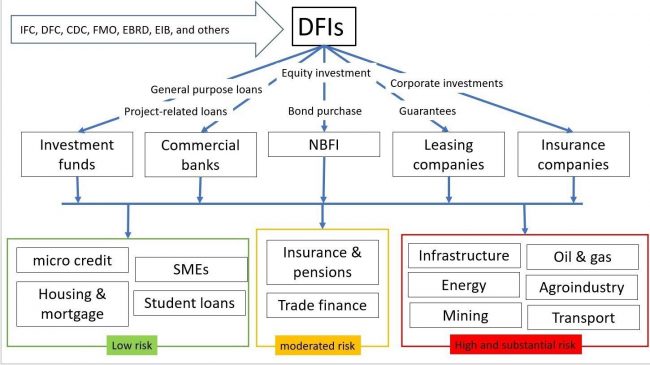

Financial intermediaries represent the nexus between development finance and commercial banking. In other words, private sector banks that receive financing from a development finance institution (DFI). DFIs use private sector banks as financial intermediaries on the premise that it will expand their development finance reach and raise the standards of the financial sector. Financial intermediaries can include commercial banks, private equity funds, leasing and insurance companies. The big question and big concern is whether DFIs can mobilize commercial finance without compromising their development mandates — with transparency and environmental and social standards as a core part of that.

Paths for DFIs to channel funds through financial intermediaries to finance projects of varying levels of risk. The risk levels shown in the graphic relate to environmental, social and governance (ESG) risk and it does not include other forms of risk such as financial risks. Photo: Oxfam International

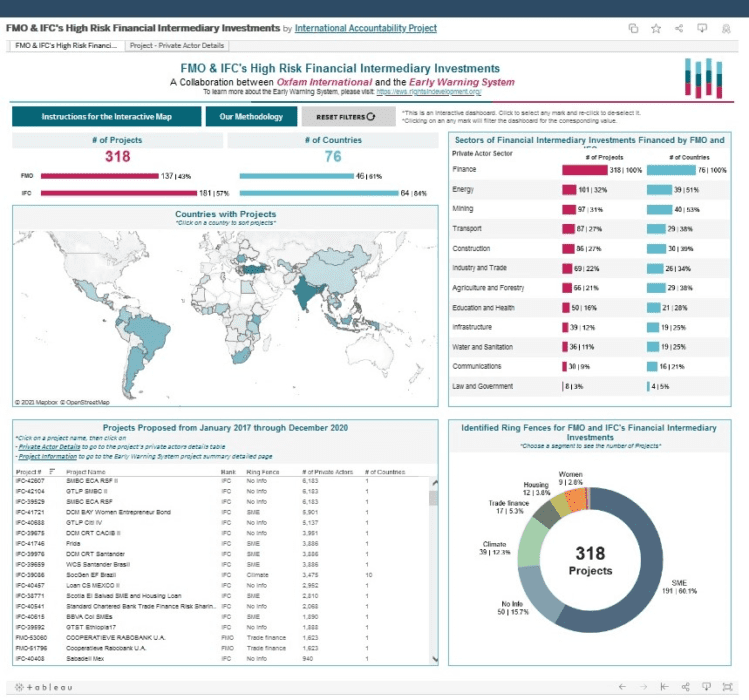

The disclosure of such basic information is important given that financial intermediary lending continues to neglect principles and standards that most development banks have in place in terms of transparency. For this reason, in 2021, Oxfam International partnered with the Profundo, the International Accountability Project and the Early Warning System to contribute to bridging this transparency gap by making information on high-risk sub-clients and sub-projects of IFC and FMO’s financial intermediary investments accessible within the database.

The Early Warning System is an initiative that seeks to ensure communities have access to verified information on projects proposed and funded by development banks that are likely to impact them. As part of Oxfam International’s Open Books’s report and research, this collaboration launches a new initiative which organizes and makes public, for the first time, new, accessible information on the high-risk sub-projects of 318 financial intermediary investments made by IFC and FMO which impact people and the environment in at least 76 countries. The data includes financial intermediary investments from 2017 through 2020. In addition to illustrating the ownership structures of these sub-clients, where this information is available, the Early Warning System database also connects each private actor to other investments made by development banks in the same company. In total, relationships among 12,800 private actors are documented and now public. The value of these investments is $38.2 billion USD.

Explore the sub-clients and sub-projects of IFC and FMO’s financial intermediary investments using this interactive data visualization. Click the project title to view project documentation in the Early Warning System Database. Download the entire list of sub-projects and sub-clients using the button on the bottom left of the visualization.

Development banks like IFC and FMO, among others, are increasingly channeling their financial support through financial intermediaries (60 and 40 per cent of their total portfolio respectively) on the premise that financial intermediaries will expand the reach of development finance and raise the standards of the finance sector. However, some of the devastating impacts of this approach to financing development projects has been well-documented in a number of projects leaving behind serious environmental destruction and entire communities being forcibly evicted.

The opacity and lack of transparency around financial intermediary investments made by development finance institutions means weak enforcement of environmental and social standards, lack of clarity regarding where such development finance ends up, and what the development impacts of such investments are. And importantly, that communities affected by these high-risk projects are left behind suffering the negative impacts not knowing who is behind those investments and what protections they have.

This year some DFIs have started a process of amending or reviewing their policies on transparency and/or financial intermediaries like the European Investment Bank where civil society has engaged providing inputs on how to improve their transparency practices.

We understand that FMO will open a public consultation process on a new Position Statement on Financial Intermediary Lending before the end of the year. FMO states that transparency on their financing and investments are fundamental to fulfilling their development mandate. Unfortunately, in practice, FMO does not disclose any information about sub projects supported via its investment in Financial Intermediary clients.

Last year the IFC became a leader among its peers by committing to require its financial intermediary clients including commercial banks to “annually report the name, location by city, and sector for subprojects funded by the proceeds from IFC”; however, we are still waiting to see how IFC discloses such basic financial intermediary subproject information in practice. We certainly expect that other DFIs will follow IFC’s lead. Meanwhile, public disclosure of information about the companies and sub-projects being financed by development finance institutions’ financial intermediary clients remains sparse and inadequate.

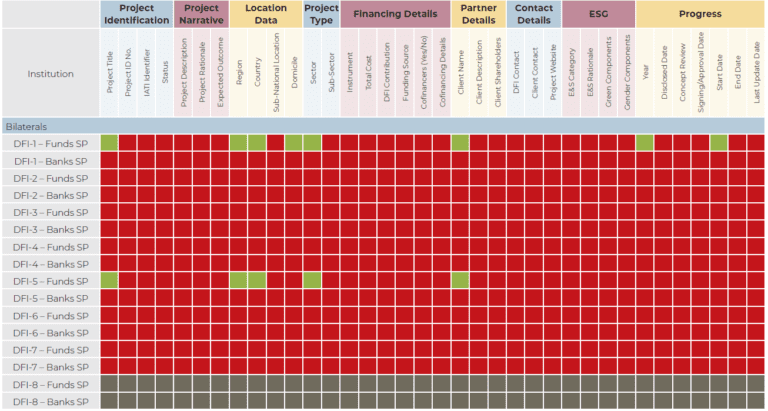

Source: Publish What You Fund’s Report: Financial Intermediaries Workstream 5 Working Paper. Financial intermediary sub-investment disclosure of basic information. Traffic light code: Green: disclosure was found; Orange: disclosure found in some; Red: no disclosure.

While there are still legitimate questions and challenges about how to disclose sub-project information of financial intermediaries, we maintain the position that access to such information is a right itself, and that (lack of) disclosure of such information by development banks and their financial intermediaries is a choice and not a legal roadblock. Development banks and their financial intermediary clients should commit to a time-bound transparency and disclosure reform agenda of disaggregated higher risk subproject-level information, develop a comprehensive transparency policy, and set up appropriate mechanisms for subproject information disclosure of higher risk subprojects and activities they engage on regardless of the financial instrument used.

This disclosure policy and system should be a core component of their environmental and social management systems and policies. While recognizing that this is the responsibility of development finance institutions like IFC and FMO to do themselves, with this financial intermediary data and through the Early Warning System, we wanted to exemplify that such disclosure is possible.

It took two NGOs and a research agency significant amount of time, resources, and working hours to put this financial intermediary data together, while it should be a basic right to have access to this information. The question is why getting access to such basic information is made so hard when development institutions like IFC, FMO, and other DFIs should have this information at their fingertips and make it accessible?

Read additional information about the Financial Intermediary data.

This post was co-authored by Christian Donaldson, Economic Justice Senior Policy Advisor at Oxfam International’s Washington Office, Imke Greven, Policy Advisor Land Rights at Oxfam Novib, and Ryan Schlief, Executive Director at the International Accountability Project.